Russia invaded Ukraine on 24 February 2022 across multiple points along their shared border. While there were initial calls of a swift Russian victory, those began to falter as time wore on and Ukrainian resistance surprised outside observers.

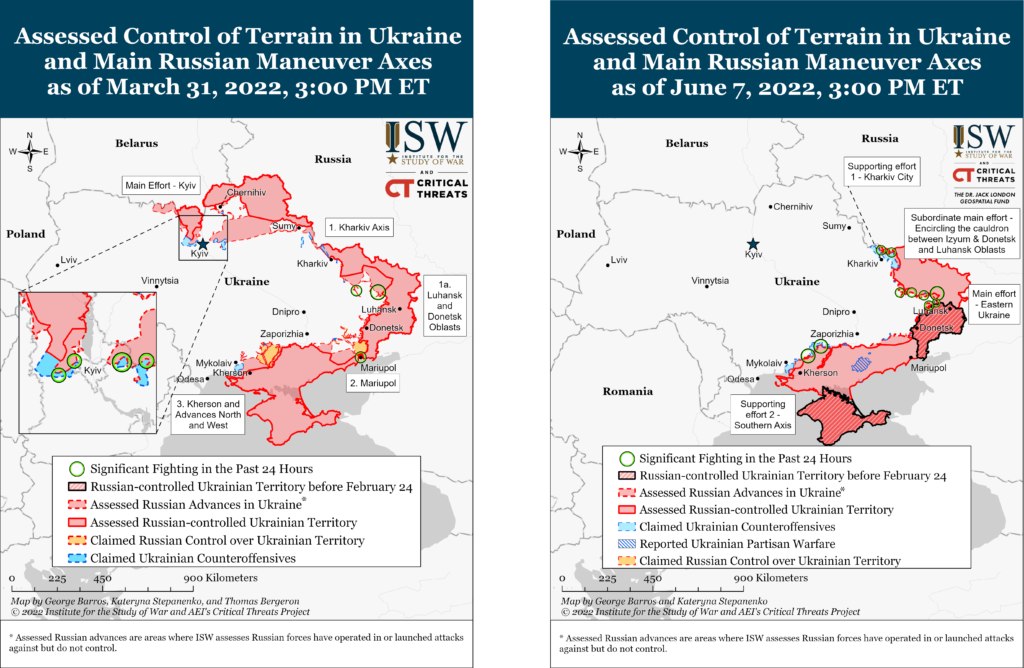

The snapshots below compare the state of Russian inroads at the end of March and early June. As you can see, the initial phase of conquest directed against Kyiv failed. Currently, Russian forces are focusing on consolidating their gains in the Southern and Eastern regions of Ukraine. This includes attempts to take over towns and cities within Luhansk, with Severodonetsk being a major point of action as of 7 June. Russian forces are also attempting to implement administrative control of occupied regions to embed these territorial gains.

Figure 1: Ukraine-Russia conflict progression – 31 March 2022 vs 7 June 2022

On the other side of the ledger, Ukrainian forces continue to be supplied by Western countries including most major European nations, the US and even Australia. This is helping to offset the material advantage Russia has in both weapons and manpower. Russia also appears unwilling to escalate the conflict further. As an example, Russian authorities have refrained from launching a formal mobilisation to increase available manpower. Instead, they have tried to actively recruit from the current pool of conscripts, as well as external mercenaries to make up for casualties amongst existing forces.

Update on base case

As Ukraine remains well-supplied from the West, and morale is holding up, the resistance looks set to continue. The picture from a Russian perspective is less clear cut. While there have been sizeable casualties, the exact number remains unknown. Having a finite supply of equipment and enlisting reservists into service suggests that there are limits on how much further the Russians can continue the conflict.

Overall, the current state of affairs suggests that an eventual peace settlement of some form is the likeliest course of action. The eventual timing remains difficult to anticipate with both Ukrainian resistance and Russian staying power continuing to surprise experts. A somewhat similar outcome in a “frozen conflict” could also occur whereby neither side pursues further conflict but ultimately, the war remains unresolved. In such a setting, we could see long-term isolation of Russia in a manner akin to the treatment of North Korea or Iran by Western powers.

Implications

An elongated conflict impacts the global economy. The primary way it does so is by constraining global supply of key commodities. These include:

- Wheat;

- Oil and gas; and

- Coal.

This is because a mix of sanctions, as well as destroyed crops and pipelines, has reduced global availability from both Ukraine and Russia. Less supply coupled with strong demand has pushed prices higher. This does not only impact the economy as the increased cost of necessities weakens discretionary spending, but it can also erode social stability as seen during the Arab Spring uprisings in 2011. The uprisings were fuelled not only by repressive regimes but also elevated food prices (notably necessities including bread). A repeat is already underway with regime change occurring in Sri Lanka as the country, a major commodity importer, has struggled materially in the face of higher prices for both energy and soft commodities.

Australia has not been immune to these global events. In recent weeks, gas prices have surged in response to moves in offshore pricing. Excluding Western Australia, the rest of the country does not have a policy in place to reserve gas for domestic use. This leaves us susceptible to changes in global market pricing. This is particularly so during surges of demand. A recent bout of cold weather on the East Coast coupled with the temporary shutdown of coal-powered plants saw gas prices surge and compel the regulator to intervene and implement cap pricing initially. This was followed by the use of emergency powers to suspend wholesale prices entirely in order to curb recent volatility and ensure continued electricity production.

The effects of this surge are twofold:

- It will boost headline inflation and be a detractor from discretionary spending at a time when consumer confidence has already softened materially (sitting at August’20 lows according to the Westpac-MI Index of Consumer Sentiment).

- Secondly, this will add to pressure on the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) to hike interest rates, slowing economic activity.

Conclusion

The conflict is ongoing and contributing meaningfully to both global and domestic inflation. It has raised the prospects of further interest rate hikes to reduce inflationary pressures, which can have the collateral impact of weakening the overall economy.

We maintain our bias towards businesses that have pricing power as these are better equipped to weather rising costs, as they can pass these on to end costumers. The overall, weaker economic backdrop is one we continue to monitor closely as it may increase recession risks with consequences for portfolio positioning.