Navigating the global Supply chain bottlenecks

Pitcher Partners Investment Services (Melbourne) | The information in this article is current as at 10 October 2022.

The advent of the Covid-19 pandemic highlighted a major fragility in global supply chains, with scarcity of key products like personal protective equipment, such as facemasks and gloves, and basic amenities such as toilet paper became hard to source.

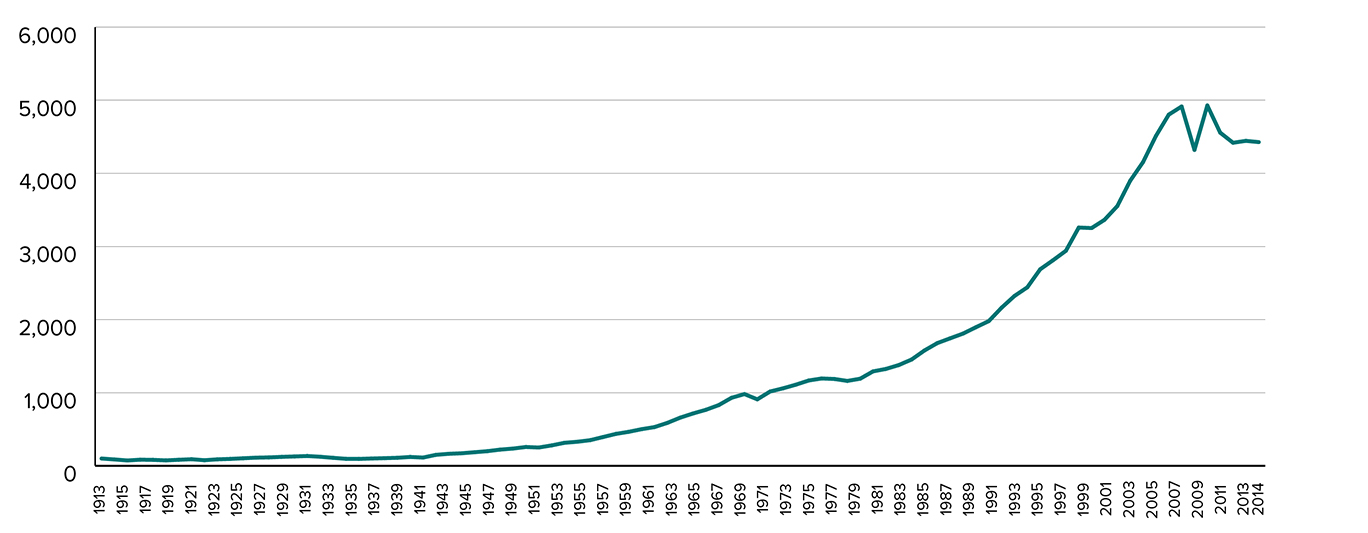

A 70-year global trade boom, initiated by the rebuild following the second world war, and an increasingly globalised world caused companies to source cheaper inputs and cheaper locations for production of goods. Since 1950, annual growth in world exports has averaged around 6% according to World in Data.

Growth in world exports (indexed to 1913 level)

Source: Our World in Data

As trade has grown and become more efficient, companies have been able to source goods from around the world, and consumers now have access to a huge variety of goods. In order to maximise benefit, this led to companies increasingly adopting a ‘just-in-time’ inventory policy, which requires a very well-oiled supply chain to function. A move to a just-in-time model helped to streamline operations, encouraged system reliability and reduced costs and financing by having goods delivered when and where they were needed. This was a far preferable outcome to having excess inventory sitting on shelves in an expensive warehouse.

But in recent years, several hurdles to the global supply chain system began to emerge. Trade disputes, responsible sourcing, and a desire to manage supply risk have all caused some early ripples. As the Covid-19 pandemic hit, causing disruption, the global supply chain was shaken.

Shutdowns and disruptions impacted the last decades race towards ‘just-in-time’ inventory management. Companies found themselves without finished goods and consumers complained of empty shelves in stores.

The disparate re-openings and ongoing pandemic measures, particularly in logistics (shipping and air freight) caused the initial impact to become a major issue, as disruptions occurred at multiple points across the global logistics networks. A lower level of investment into supply chain infrastructure (maritime vessels, port infrastructure etc.) for some years also had an impact, lowering the availability of key transport and putting additional pressure onto an already thinly spread transport industry.

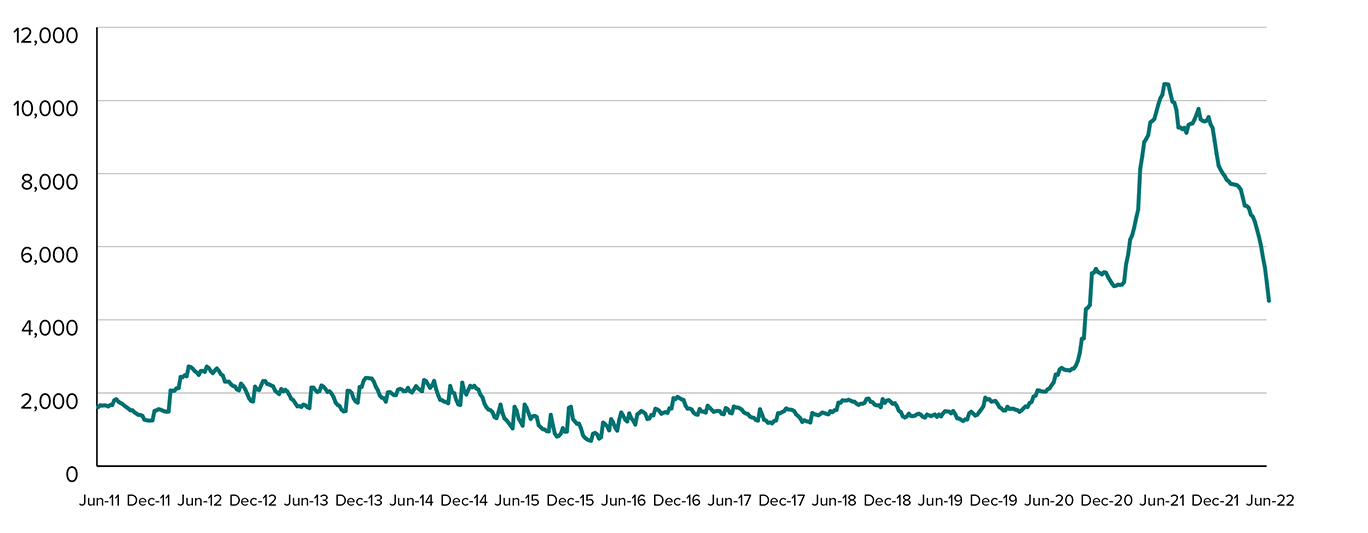

Composite container freight benchmark rate (40ft) – shipping freight rates

Source: Drewry World Container Index, Bloomberg

These factors affected companies across the spectrum, with heavyweight brands such as Apple, Tesla, Amazon, Estee Lauder and others, all facing difficulties sourcing supply of parts and getting products to market. The entire automotive manufacturing industry was hostage to a shortage of semiconductor chips, and retailers were left with a shortage of stock on the shelves for consumers.

A confluence of factors had caused damage to supply chains, among them Covid, but also the beginning of central bank tightening, trade tensions and responsible sourcing considerations.

Due to Covid-caused bottlenecks that emerged, many companies, particularly retailers, stated a willingness to hold higher than normal levels of inventory, to be able to satisfy consumer demand. A higher level of inventory (and its concurrent risks) was seen as preferable to empty shelves seen at times during the pandemic.

As the pandemic progressed, and supply issues remained, retailers increased orders to account for supply-chain related delays, resulting in further pressure on the supply chain, and skyrocketing costs to deliver goods.

The ‘just-in-time’ model was replaced by the ‘just-in-case’ model with companies preferring to have stock available and run the risk of higher inventories, than not have any stock available for customers.

Shutdown of ports and factories in parts of Asia elsewhere brought major disruptions. Added to this, companies dramatically lowered their production expectations going forward, expecting a prolonged global slowdown, which did not eventuate. As consumer spending remained resilient throughout the pandemic, the shift in spending patterns exposed further difficulties in the supply chains.

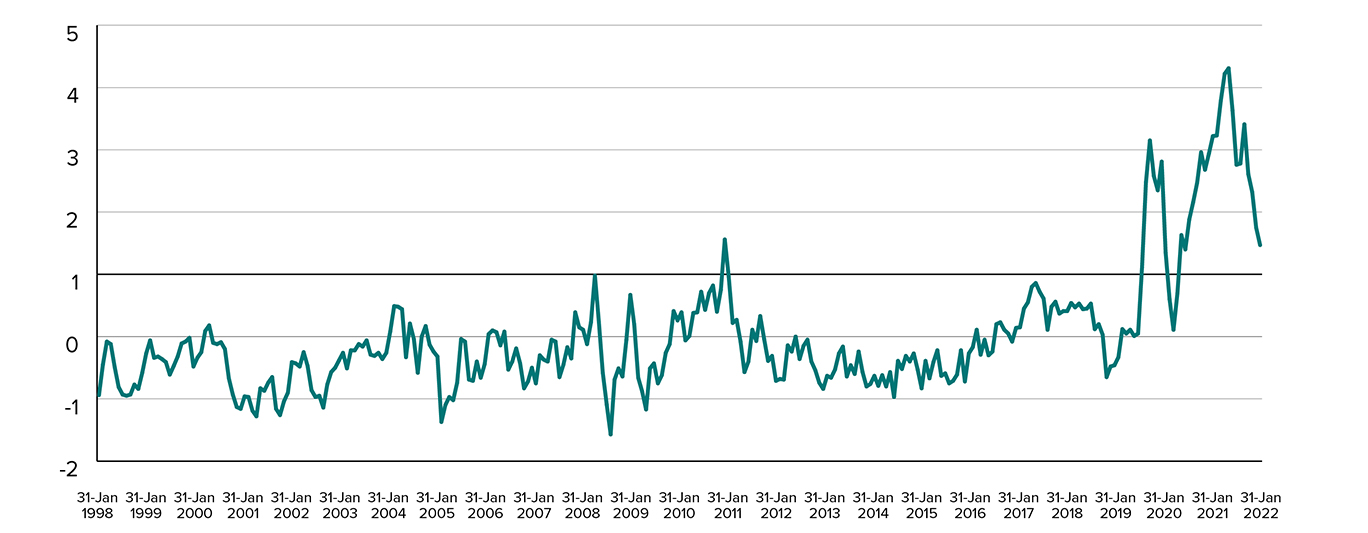

The bottlenecks in the supply chain have gradually been easing in recent months, partly due to continued operation of ports, logistics and factories in manufacturing hubs like China, and also as some of the inventory has gradually made its way through the system. A global supply chain pressure index, developed by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, shows an easing in recent months, albeit still at elevated levels.

Global supply chain pressure index

Explainer: Readings above zero indicate building pressure, below zero indicate easing pressure.

Source: Federal Reserve Banks of New York, Bloomberg

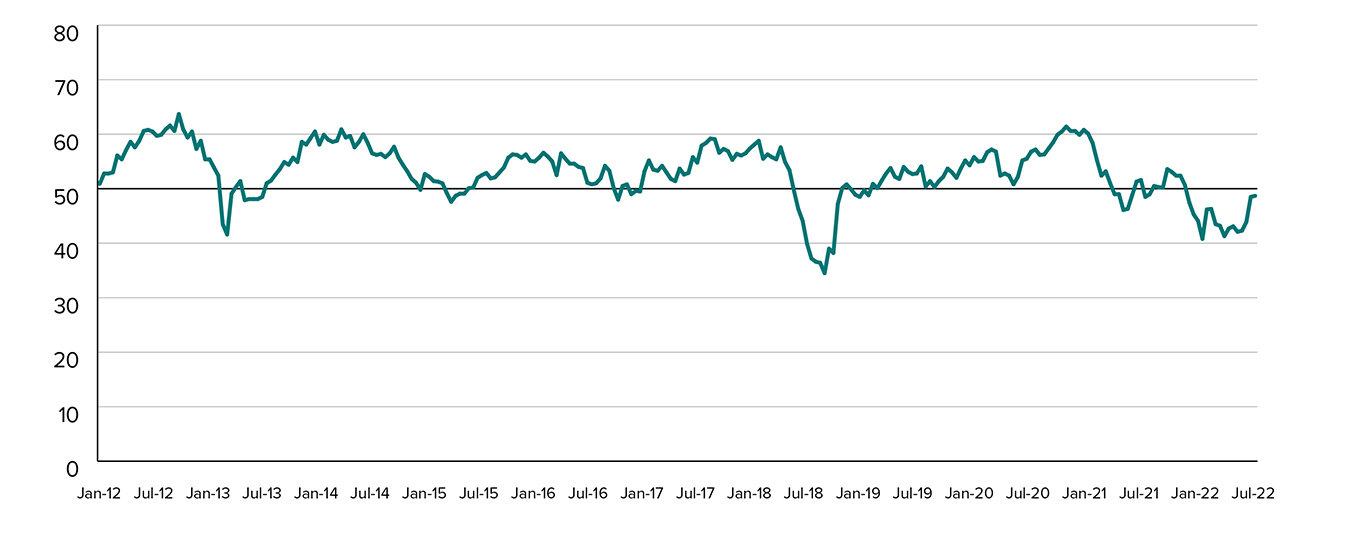

Lower global demand is playing a key role reducing bottlenecks. Global Purchasing Managers Index have begun falling, and supply chains are now increasingly becoming clogged with inventory.

There is no straightforward solution to these emerging issues. Recent decades of shifting production of goods to places like China are difficult to unwind. Recent analysis by Bloomberg Intelligence shows that a behemoth like Apple would take 8 years to shift 10% of its production capacity out of China. Re-engineering the entire global supply chain is therefore not a viable solution.

However, as easing of supply chain pressures began, the risk of excess inventories is becoming real, as orders from companies anticipating continued difficulties securing supply have been ramped up, meets a slowing consumption environment. Demand conditions have been easing, and are expected to ease further, as rising interest rates and slowing economies impact consumer end-demand across the Western world. This could bring further problems to retailers, in particular, as they sit on higher-than-normal levels of inventory.

US purchasing managers index – new orders

Explainer: A reading above 50 indicates expansion, below 50 is contraction

Source: Institute for Supply Management, Bloomberg

Several looming issues also pose a risk for supply chains returning to normal in the next few years. The increased attention on environmental, social and governance has brought more focus on the role and practices of the various firms that supply parts, and increasingly pressures on firms to take responsibility for the products and inputs they are buying from suppliers and ensure that sourcing of goods and inputs into the production cycle are from suppliers operating in a responsible manner.

Tight labour markets continue to pose a challenge, with wage inflation and lower mobility of workers during the pandemic have escalated costs and reduced availability of skilled workers.

National security will also likely become an increasingly relevant factor, as seen in recent bans by the US government to forbid the export of certain semiconductor chips to China. These types of trade restrictions are likely to create further headaches in the global supply chains.

From an investment point of view, being prudent and treading carefully will be key. Avoiding potential earnings surprises from stocks carrying excess inventory and facing earnings downgrades from a slowing environment will be increasingly needed.

Prior to the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, supply chains were generally in the background, invisible, and largely irrelevant to many investors. But recent events have highlighted vulnerability of the supply chain to external shocks. Going forward, investors will likely need to take supply chains more into consideration when analysing potential investment opportunities.