Pitcher Partners Investment Services (Melbourne) | The information in this article is current as at 7 July 2022.

The overall Energy sector and there are many parts to it, is probably one of the most talked about sectors in the markets currently, taking into account all the issues in Europe and the global economy along with managing the Energy transition.

Today, I am joined by Adrian Prendergast – Senior Research Analyst at Morgans Financial Ltd who kindly provided some time to discuss many of the key issues on investors minds.

Alistair Francis: Can I start by asking you, that given the terrible situation with respect to the Russia & Ukraine war, how important is Russia to global supply of the two key Energy sources, namely Oil followed by Gas?

Adrian Prendergast: For oil, Russian supply is critical for two reasons:

- it accounts for a whopping ~11% of global oil production (~10.8mb/d), and

- at the start of the year we had forecast Russia to be one of the only sources of supply growth globally in 2022 (~1.0mb/d).

We estimate that the sanctions levelled against Russian crude has impacted an amazing ~7.0mb/d of supply. While some sanctioned Russian supply is likely still finding its way into global oil markets via Russia’s remaining trading partners (China and India), there is no disputing the sanctions have added to existing 1.1mb/d supply deficit that oil started the year with and supported oil prices well north of US$100 per barrel.

Gas is a far more complex picture. This is because of gas’ dependence on capital-intensive infrastructure to produce and transport it. With little prior regard for energy security, major Western European nations have steadily increased their dependence on Russian gas, which in 2021 accounted for 45% of European Union gas imports. While it will take years for European countries to shift away from their high dependence Russian pipeline gas, the tectonic shift in the geopolitical landscape that has resulted from the Russia-Ukraine conflict is likely to have a structural impact and shift more demand to seaborne LNG markets.

Alistair Francis: I guess the current situation in China with a Covid Zero policy also makes forecasting the level of Oil & Gas demand also quite problematic?

Adrian Prendergast: It has made forecasting global demand incredibly difficult. Particularly with the Chinese government sticking to its Zero Covid policy. This is important to global energy markets given China is a key contributor to both oil and gas demand growth. Also hard to analyse is how much Russian oil and gas China will start to consume above its typical levels, given their ongoing trade relationship.

Alistair Francis: Will it be easy for the global Oil & Gas producers to replace Russian supply that is likely to be embargoed due to global sanctions for many years ahead?

Adrian Prendergast: We see little potential to fill the ‘Russia gap’ in oil supply. The best alternative supply source should be the US, although oil production in the US has also failed to live up to expectations. US production growth has been materially limited by stretched balance sheets and poor business and investor confidence (helped in no small part by the global energy transition to greener energy resources). The other key supply feature has been the potential for a new nuclear agreement with Iran, although we only see this as having potential to unlock 1.5mb/d of new supply. Meanwhile oil stockpile releases from various key consuming countries have only had limited and temporary effect.

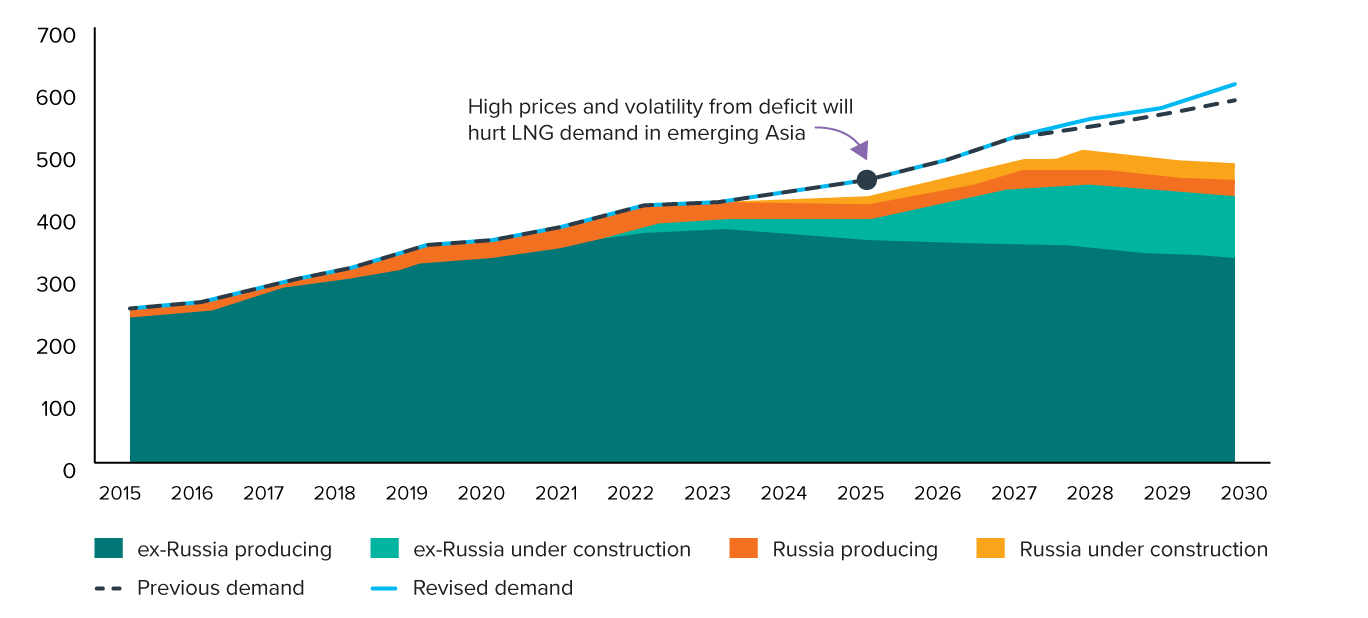

Gas is a different story. Unlike oil, which is supply/investment constrained, we see medium and long-term global gas supply as better supported with significant growth projects in the US, Africa and Qatar. Although this supply is still some way off with global gas prices likely to remain elevated above long-term sustaining levels for the next 3-5 years.

Global LNG supply and demand outlook

Million tonnes

Source: Rystad Energy GasMarketsCube, Rystad Energy research and analysis. May 10, 2022

Alistair Francis: Typically today, how long does it take say for a green-fields development once drilled out to bring that oil or gas to market?

Adrian Prendergast: The average would be 10-15 years from discovery to first production.

Alistair Francis: Pre-Covid, the market was talking up the enormous oil supply coming on-stream from the US due the fracking boom. For our audience, briefly explain what is fracking and then where has all that additional supply gone?

Adrian Prendergast: Simply put, shale is a type of rock that oil is not normally recovered from in an economic quantity. This is due to the difficulty oil has in travelling through and accumulating in shale rock versus some other types of rock such as sandstone for example. In the last decade however, technological innovation has found a way to efficiently recover the small amounts of oil (and gas) found in shale rock in oil and gas prone areas. These innovations are: 1) horizontal drilling (allowing wells to be drilled along large amounts of shale rather than just ‘puncturing it’ with a vertical well) and 2) fracking (using a great deal of force to break up the hard shale rock and release the oil held).

The problem with the shale oil model is how capital-intensive it is. Each individual well only recovers a small amount of oil and typically 70-80% of total production from that well is recovered in the first 12-18 months. These two factors mean that shale producers have to keep drilling and fracking continuously to sustain their overall oil production as the production from shale wells are constantly falling off and needing offsetting with new production. As you can imagine this is not a capital efficient business model, and has only been made possible by these shale producers sourcing external capital from debt and equity markets to grow their production. However this access to capital has been severely damaged over the last six years with two once-in-a-decade downcycles in oil prices (2016 & 2020). As a result, even with cash margins now at buoyant levels, a large portion of shale producers still lack the balance sheet capacity (capital resources) to be able to reinvest in new production despite the healthy margins on offer. A secondary constraint has been supply-chain bottlenecks (shortages of frac sands and crews, drill rigs, etc).

Alistair Francis: I guess on the other side of the ledger is demand. When is the growing impact of EV’s or the use of alternative fuels likely to make a greater impact on global oil demand?

Adrian Prendergast: The substitution to EV’s has started from a low base, but is likely to have a cumulative impact on global oil demand as these markets continue to grow. Our most aggressive modelling of these trends points to oil demand [changing by] -1% per annum by the late 2020’s. This is interesting when we match it up with supply dynamics. Production from oil fields all naturally decline over time, as a global industry that rate is declining approximately 4% per annum. This means without new supply investment the demand-supply balance would still [be off by] a material rate of -3% per annum. While long-term supporters of a greener future for our planet, the above equation highlights the need for an actual smooth transition (i.e. ongoing investment in oil supply, as well as battery materials).

Alistair Francis: What about the impact on global LNG demand from the energy transition?

Adrian Prendergast: At the heart of LNG’s position in the energy transition is the fact that the global energy mix can only pivot so fast. At present over three quarters of the global energy mix is made up of fossil fuels. With this in mind, LNG will is an effective enabler of the energy transition given it is less carbon intensive versus thermal coal and oil. Therefore, in the medium term, growth in LNG supply will help the world pivot away from coal and oil use.

Alistair Francis: Given the tighter global gas market, are Australian gas producers reasonably well positioned with new supply coming on?

Adrian Prendergast: WDS – Woodside is in a solid position given its LNG portfolio, and growth projects in Western Australia and Trinidad & Tobago. Importantly, the recent merger with BHP Petroleum also more than halved gearing, which we estimate now stands at approximately 10%, allowing Woodside to continue pursuing new growth while supporting a strong dividend. A key strength is Woodside’s exceptionally deep marketing relationships in the LNG market and stellar reputation as a tier 1 operator. This positions Woodside to attract key customer support for growth and confidence in leading joint ventures.

STO – Santos has transformed as business over the last 6 years, and is now a formidable diversified oil and gas producer. Unlike Woodside’s concentrated portfolio of LNG and domestic gas operations, Santos holds a highly diversified oil, gas and LNG business spanning Australia, PNG and Alaska. In terms of gas, Santos’ key assets include its PNG LNG, GLNG, Darwin LNG, and sizeable WA domestic gas business. Santos is pursuing growth across several parts of its portfolio, while also is expected to benefit from selling down minority stakes in projects such as PNG LNG and Dorado.

Alistair Francis: Over the past few years, there has been a greater push by listed energy companies to raise their capex budgets to find ways to reduce carbon emissions. Can you give us some examples of where this spend is taking place?

Adrian Prendergast: Capex budgets are certainly trending higher, as is the management focus of these companies on reducing carbon emissions. Australian listed energy companies appear to predominantly be coming at it from the perspective of sooner or later decarbonising is going to become a licence to operate. A major focus for larger energy companies are pursuing carbon capture & storage (CCS) projects, although these are technically difficult and can be capital intensive, leaving the energy industry so far waiting on government support before executing. In the case of Woodside it is also pursuing hydrogen as a core focus, believing that the return profile may start off low but will develop (along with the hydrogen market) in time. Where we have seen energy companies purchase carbon credits has been mostly in instances where they cannot displace the carbon from their business themselves (such as Scope 3 emissions). This is more common amongst smaller oil and gas producers who lack the capital resources, technical expertise, and/or operating scale to decarbonise more aggressively through innovation.

Alistair Francis: Carbon capture storage (CCS) is a technology that I believe has been around since the 1970’s, can you explain how both WPL and STO positioned in using this technology

[Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is the process of capturing and storing carbon dioxide (CO2) before it is released into the atmosphere.]

Adrian Prendergast: Both Woodside and Santos are well positioned to pursue CCS, which appears a key focus for both companies. Each company have aging long-life gas fields (North West Shell fields for Woodside and Cooper Basin / Bayu Undan for Santos) which can be converted into carbon storage. There are 27 operational CCS projects in North America, with more than 100 currently in construction. This followed positive fiscal regime changes, which moved to support CCS. We expect this rush of project builds will significantly advance CCS best practice, which both Woodside and Santos will benefit from.

Alistair Francis: Why is Andrew Forrest from Fortescue Group regularly criticising the technology?

Adrian Prendergast: Fortescue is in a poor position to pursue CCS given its lack of existing fields that it can use for storage and lack of technical energy understanding. This has not stopped Fortescue investing aggressively in other green areas such as hydrogen, but CCS does appear a bridge too far.