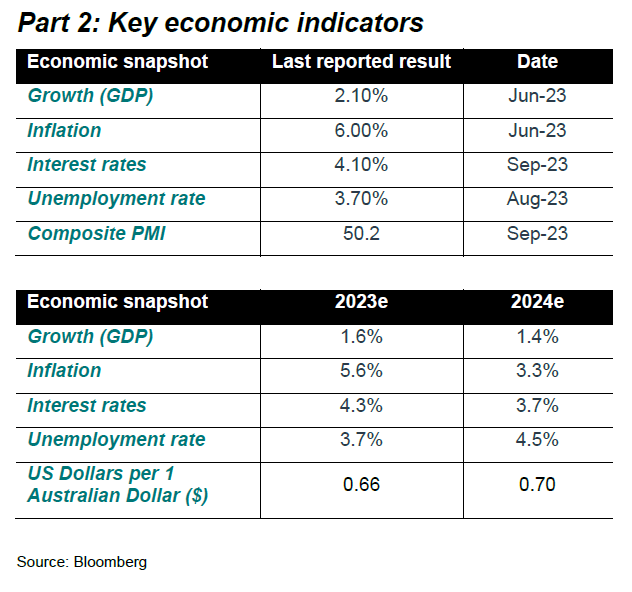

In recent months, the impacts of the 400-basis point interest rate hikes since May 2022 have been plain to see.

Higher interest rates have reduced disposable incomes of mortgage holders. This cohort has begun to cut back on discretionary spending as evidenced by several recent earnings downgrades from prominent retailers including Harvey Norman, Adairs, Best & Less & Super Retail Group. Supermarkets too have been reporting a rotation to cheaper home brand items as consumers tighten their belts10. It is perhaps no surprise then that the National accounts for the year ending 30 June (released in September) showed that the economy is in a per capita recession, as defined by two consecutive quarters of negative growth (-0.3%, -0.3%)11 per capita.

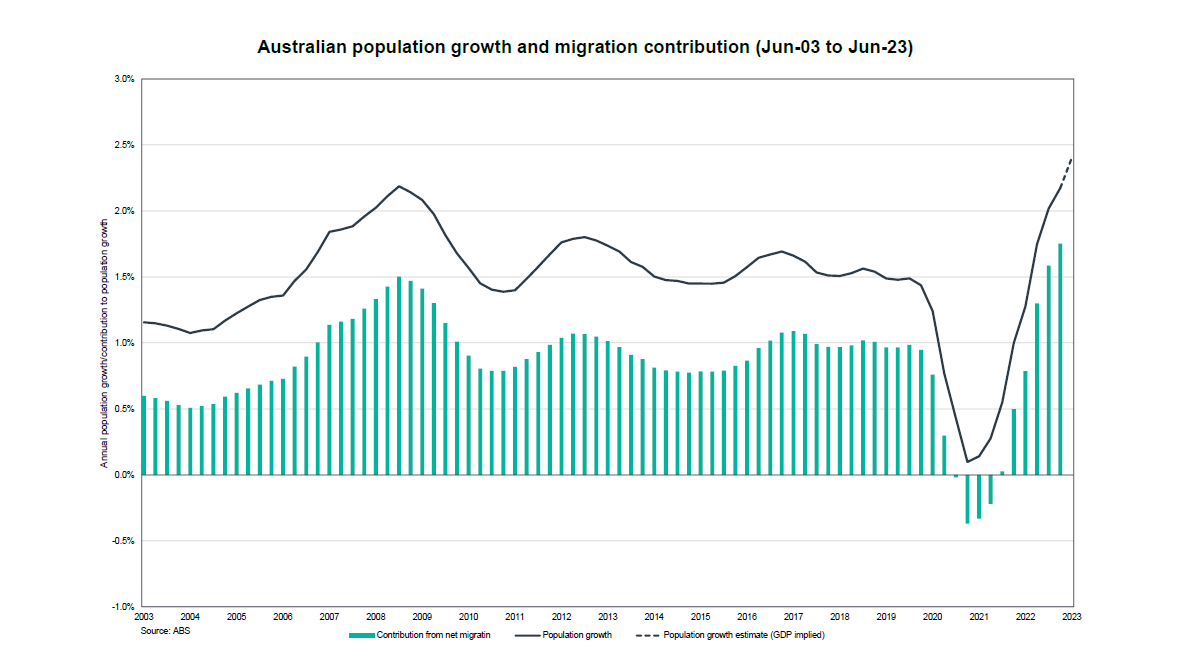

Yet despite a decline in average household demand, the economy still grew over the year by 2.1%12 overall. This outcome was driven by a very strong increase in immigration. Although the average person is spending less, the total aggregate spend is still higher due to a 2.2% increase in the population, including an extra 454,400 migrants. According to the latest GDP figures this impact was even higher for the June quarter with overall population growth at near 50-year highs of 2.4% as shown below with the contribution from migration in teal.

It is interesting that the RBA is trying to slow the economy on the one hand by raising rates to quell demand. On the other, the government is working against the RBA by encouraging record new arrivals, which only serves to stimulates the economy (more people add to total spending).

Another example of an unintended consequence is evident in Australia’s housing crisis. Millions of Australians have been impacted by surging rents as demand for housing exceeds supply. In recognition that the rental crisis will only be solved by increasing supply, the Albanese government has announced a range of measures over the last 12 months including a $10 billion Housing Australia Future Fund13 and a national target to build 1.2 million homes over 5 years from 1 July 202414. While all laudable initiatives, the increase in immigration will only make efforts to solve the housing problem even more challenging.

The immigration story is a legacy of the pandemic. In the early stages, many international students, and foreign workers on working visas went back to their homelands. The subsequent shortage of workers when Covid ended, and pent-up demand boomed, is well known. In response, the government ramped up its intake of new arrivals. Now that we have seen workers re-enter the country in droves, you would expect the labour shortage to have normalised. Indeed, in the face of weakening demand, you would expect to have seen unemployment drift materially higher.

Yet this has not been the case. Although immigration itself creates demand and jobs, it would seem the main reason why the labour market has remained tight, based on labour force data, is because of the NDIS (along with mining and professional services15). The NDIS only became fully implemented across all states just before the pandemic in 2020. There are now reportedly some 500,00016 people obtaining NDIS support, which has created a huge boom in new jobs in recent years in all the industries setup to provide support services. So, while the economy is slowing, unemployment queues have not yet materially lengthened.

Conclusion

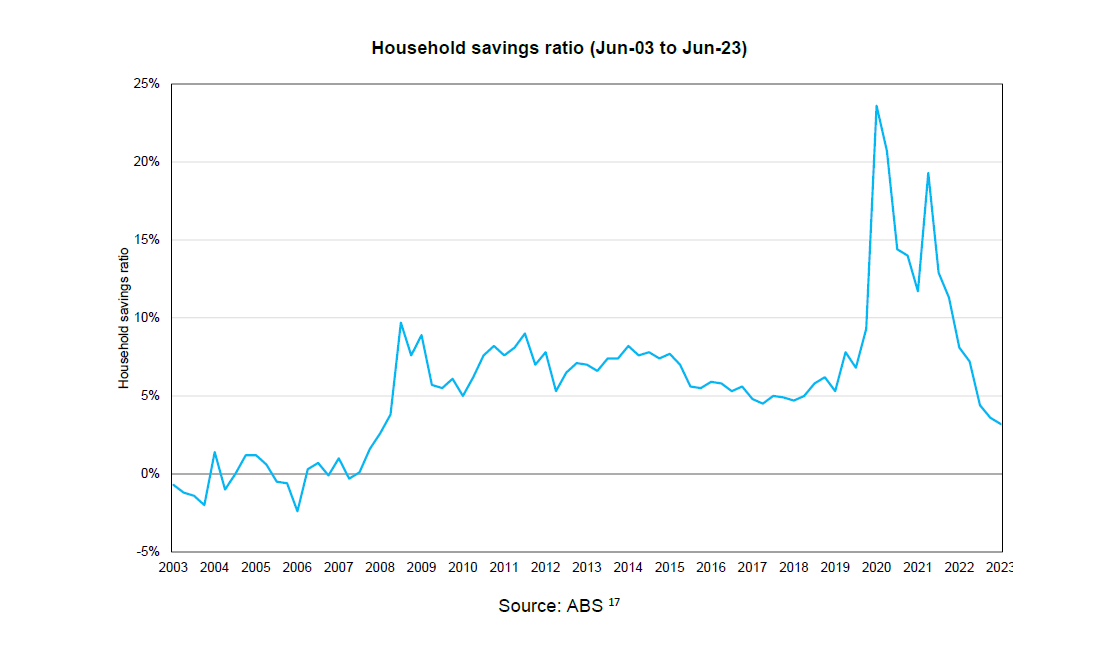

In our view there is little doubt that the economy will continue to slow over the next six months. Household spending is likely to fade as more fixed rate mortgages roll-off onto materially higher rates, eroding savings buffers. Businesses face higher refinancing costs as debts mature, and new export orders will ease as growth in China, and the rest of the world, remains anaemic. The issue that is less clear is whether the net outcome results in an economic soft (mild increase in unemployment) or hard landing (recession that creates a sharp increase in unemployment). This remains very much contingent on the RBA and its response to inflation.

On the one hand, the RBA should now be acutely aware that its policy decisions have already done enough to slow the economy. This supports the case for an interest rate cut within the next six months. On the other hand, the RBA will also be aware that a cash rate of 4.10% is only marginally above their most recent estimate of a neutral rate of 3.80%. The ‘neutral rate’ is a theoretical cash rate which is supposed to be neither restrictive nor stimulative to the economy. As the US Federal Reserve have set more restrictive rates, the consequential interest rate differential has lowered the AUD relative to the USD (and other currencies) and increased the cost of imported products, including key inputs such as oil. Further, services inflation, including rent, electricity, and insurances, remains stubbornly high.

Based on these circumstances, it would not be surprising if the RBA does not reduce rates until more evidence emerges of a softening in services inflation. As the adjustment in the price of services is typically much slower than goods, this may well delay any interest rate cut for much longer, which could increase the duration of the downturn.