Australian economy

The information in this article is current as of 1 January 2024.

The resilience of the Australian economy in the face of 425 basis point rise in the official cash rate has been well documented. Much of this resilience can be attributed to the extraordinary monetary and fiscal stimulus pumped into the economy during the pandemic.

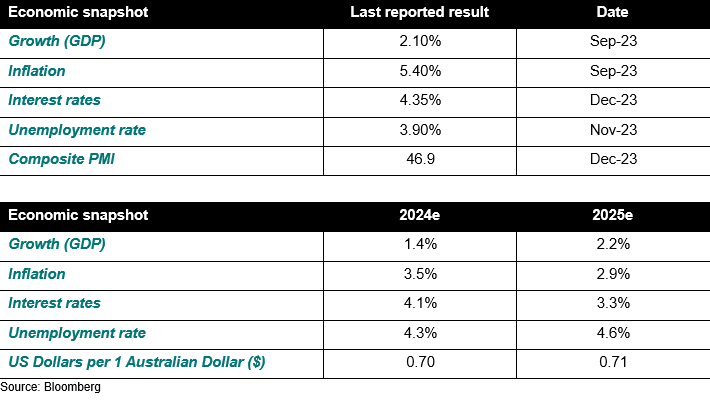

Until recently, this fiscal stimulus had been estimated at about $330bn but a new analysis by respected economist, Chris Murphy, suggests that the actual magnitude was closer to $430bn, or around 16% of GDP.

Budget cost of COVID-era fiscal policy measure ($ billions)

Source: Sydney Morning Herald

Much of this stimulus was initially saved by households as shown by the household savings ratio chart below. After peaking at almost 24%, this buffer has been rapidly depleted over the last few years as the potent combination of high interest rates and high inflation have caused households to raid their savings in order to make ends meet. The September quarter National accounts show that the ratio has now fallen to only 1.1%[1], the lowest level since 2007, and is on track to be fully depleted by mid-2024.

Household saving ratio (Sep-03 to Sept-23)

Source: Bloomberg

It is no coincidence that recent economic data has begun to weaken as this buffer has been progressively eroded. The economy grew by just 0.2% in the September quarter. Data since then has been no better. October retail sales fell by 0.2%[1]. Unemployment in November rose to 3.9%[2] due to a higher participation rate as more people began looking for work. A recent survey by the National Australia Bank showed that 44%[3] (well above the series average of 37%) of participants experienced some form of hardship in the September quarter. Over a quarter said the hardship was due to insufficient funds to cover an emergency and 20% did not have enough for food and basic necessities. Those most impacted were those on low incomes and/or large mortgages.

The Federal Government is acutely aware of these cost-of-living pressures and has begun unwinding policies that have been contributing to inflationary pressures as it is only when inflation is contained can price rises ease and interest rates be cut. In our October commentary, we were critical of the government’s immigration policy, which had allowed over 500,00 new entrants in the year to June, putting upward pressure on rents and housing prices, as well as general aggregate demand. So, while the RBA was deliberately trying to slow the economy by increasing interest rates, the Government was actively working against it.

In recognition of this unintended consequence, on 11 December the Government released a new migration strategy[4] designed to slow net migration back to pre-pandemic levels (235,000 per year by 2026-27). In addition, a day earlier, the Government announced[5] further measures to curb foreign property investors to partially address housing supply and affordability issues. These measures include tripling fees for foreigners who buy established houses in Australia and a doubling in penalties for those who leave dwellings vacant. Importantly, the Government has not extended these restrictions to new housing developments and is encouraging foreign investment in build to rent projects. It is aware that increasing the supply of new housing remains the key to solving the housing crisis and to prevent spiralling rents.

The Government’s biggest contribution to the fight against inflation, however, has been its fiscal restraint. In the December mid-year economic and fiscal[1] outlook, the Treasurer Jim Chalmers, significantly revised down estimates for the budget deficit this financial year from $13.9 billion to just over $1 billion. While the incumbent Government cannot take credit for higher tax revenues from strong mining sector profits and higher employment, it has resisted the temptation to spend this windfall revenue gain, which would have only added to aggregate demand and increased inflationary pressures.

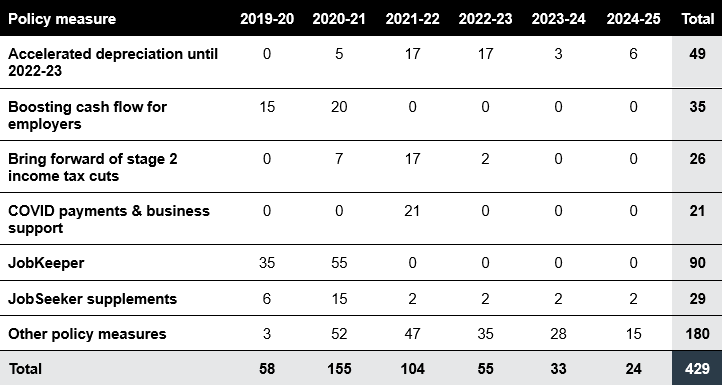

As a consequence of the RBA rate hikes and government fiscal restraint, further evidence of inflation subsiding has continued to emerge in recent months. Indeed, inflation has decreased from a peak of 8.4% in December 2022 to 4.9% at the end of October. In recognition of this trend, the RBA paused in December but has been careful to avoid language that might suggest rates have peaked, in case that helps de-anchor expectations and reignites demand. Yet with global goods inflation largely back to pre-pandemic levels, and the domestic economy continuing to slow, the case for the RBA hiking again is now weak. Further, a forecast rise in unemployment in 2024 is likely to contain wage price pressures and moderate services inflation.

Australian Unemployment Rate v ANZ-Indeed Job Ads

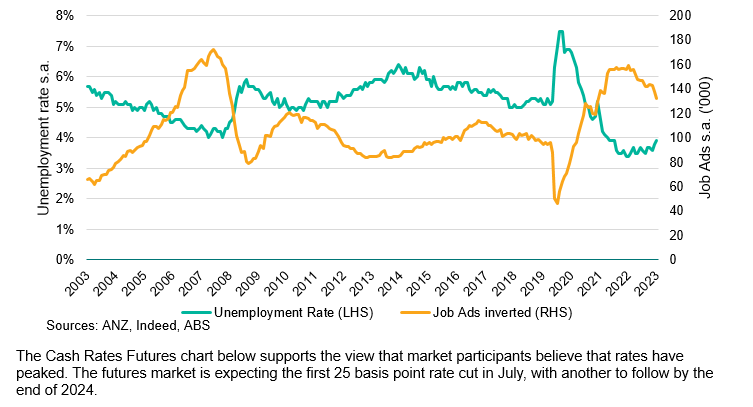

The Cash Rates Futures chart below supports the view that market participants believe that rates have peaked. The futures market is expecting the first 25 basis point rate cut in July, with another to follow by the end of 2024.

RBA cash rate forecast (Jan-24 to Jun-25)

Conclusion

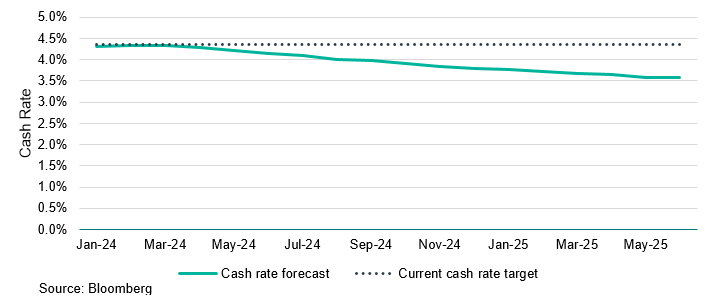

The Australian economy is expected to continue to slow in 2024 as savings are eroded and high interest rates continue to crimp household spending. The effects are likely to become more pronounced as job losses in discretionary retail and financial services start to rise. The economy however is likely to avoid a recession due to high net migration and employment levels that still remain high by historical standards. In summary, Treasury expect the economy to grow by 1.75%[1] over this financial year (FY24) and by 2.25% in FY25. Unemployment is expected to rise modestly to 4.25% and 4.5%[2] over the same periods.

Part 2: Key economic indicators